MASTG-TECH-0037: Symbolic Execution

Symbolic execution is a very useful technique to have in your toolbox, especially while dealing with problems where you need to find a correct input for reaching a certain block of code. In this section, we will solve a simple Android crackme by using the Angr binary analysis framework as our symbolic execution engine.

To demonstrate this technique, we'll use a crackme called Android License Validator. The crackme consists of a single ELF executable file, which can be executed on any Android device by following the instructions below:

$ adb push validate /data/local/tmp

[100%] /data/local/tmp/validate

$ adb shell chmod 755 /data/local/tmp/validate

$ adb shell /data/local/tmp/validate

Usage: ./validate <serial>

$ adb shell /data/local/tmp/validate 12345

Incorrect serial (wrong format).

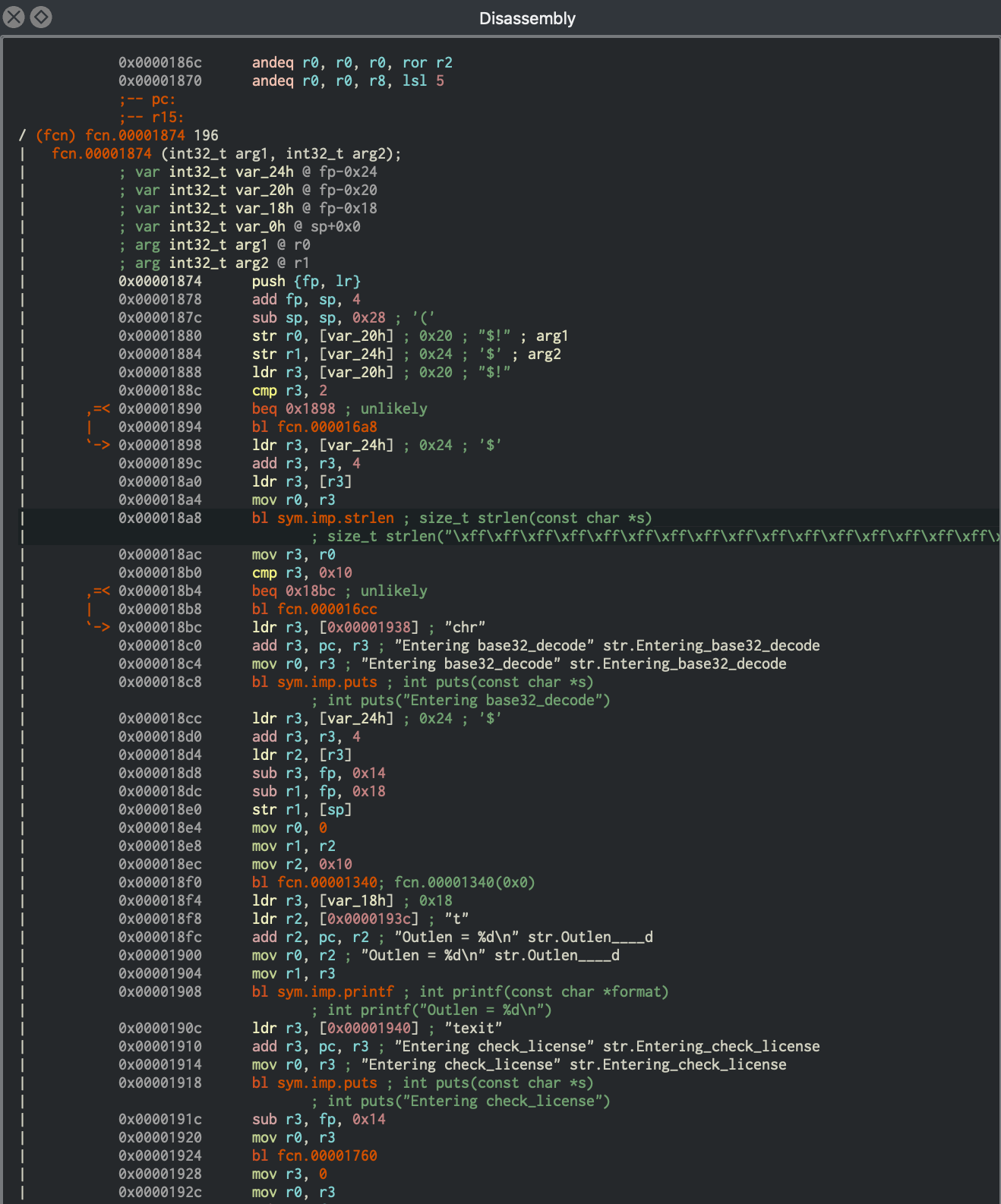

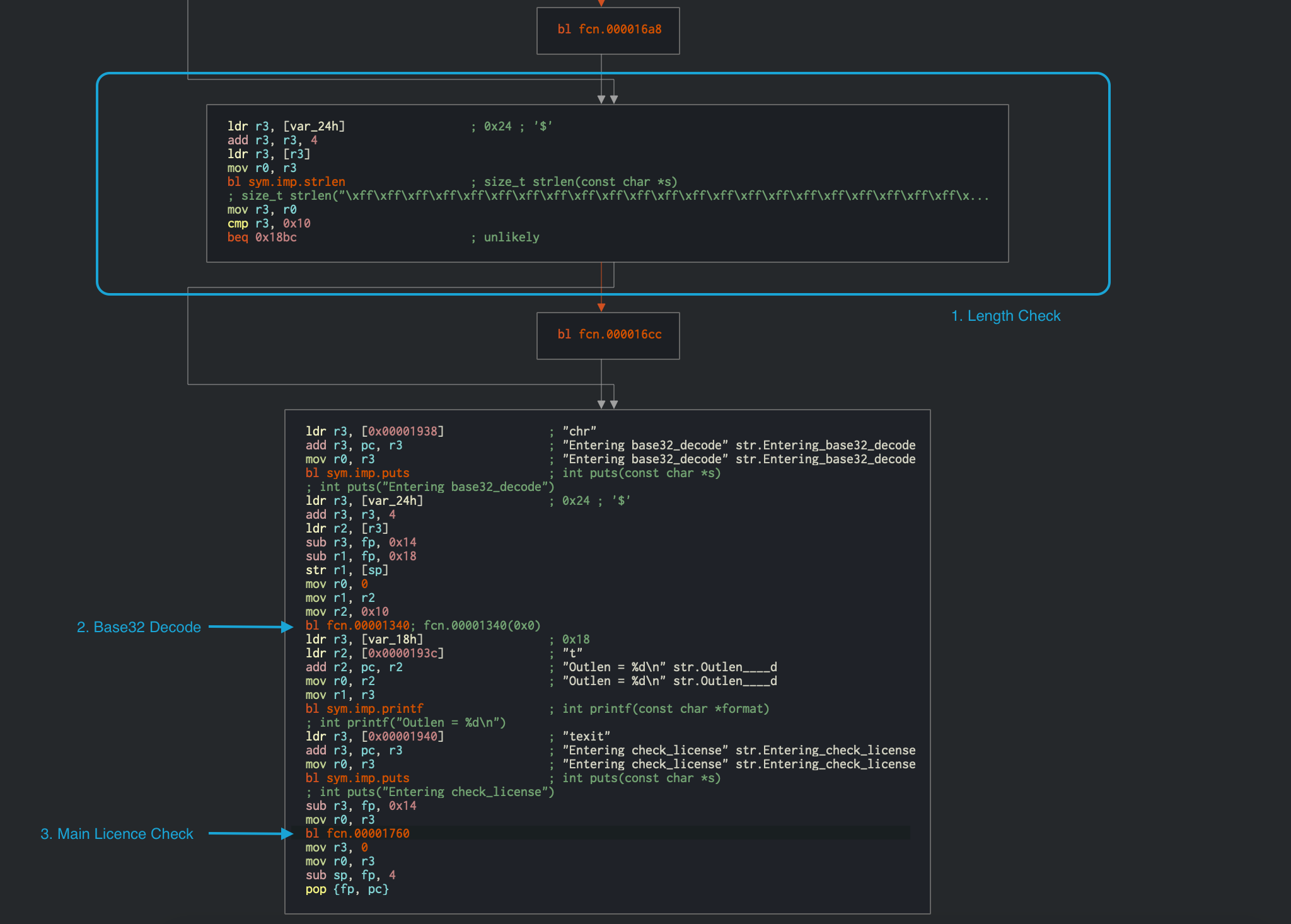

So far, so good, but we know nothing about what a valid license key looks like. To get started, open the ELF executable in a disassembler such as iaito. The main function is located at offset 0x00001874 in the disassembly. It is important to note that this binary is PIE-enabled, and iaito chooses to load the binary at 0x0 as the image base address.

The function names have been stripped from the binary, but luckily, there are enough debugging strings to provide us with a context for the code. Moving forward, we will start analyzing the binary from the entry function at offset 0x00001874, and keep a note of all the information easily available to us. During this analysis, we will also try to identify the code regions that are suitable for symbolic execution.

strlen is called at offset 0x000018a8, and the returned value is compared to 0x10 at offset 0x000018b0. Immediately after that, the input string is passed to a Base32 decoding function at offset 0x00001340. This provides us with valuable information that the input license key is a Base32-encoded 16-character string (which totals 10 bytes in raw). The decoded input is then passed to the function at offset 0x00001760, which validates the license key. The disassembly of this function is shown below.

We can now use this information about the expected input to further look into the validation function at 0x00001760.

╭ (fcn) fcn.00001760 268

│ fcn.00001760 (int32_t arg1);

│ ; var int32_t var_20h @ fp-0x20

│ ; var int32_t var_14h @ fp-0x14

│ ; var int32_t var_10h @ fp-0x10

│ ; arg int32_t arg1 @ r0

│ ; CALL XREF from fcn.00001760 (+0x1c4)

│ 0x00001760 push {r4, fp, lr}

│ 0x00001764 add fp, sp, 8

│ 0x00001768 sub sp, sp, 0x1c

│ 0x0000176c str r0, [var_20h] ; 0x20 ; "$!" ; arg1

│ 0x00001770 ldr r3, [var_20h] ; 0x20 ; "$!" ; entry.preinit0

│ 0x00001774 str r3, [var_10h] ; str.

│ ; 0x10

│ 0x00001778 mov r3, 0

│ 0x0000177c str r3, [var_14h] ; 0x14

│ ╭─< 0x00001780 b 0x17d0

│ │ ; CODE XREF from fcn.00001760 (0x17d8)

│ ╭──> 0x00001784 ldr r3, [var_10h] ; str.

│ │ ; 0x10 ; entry.preinit0

│ ╎│ 0x00001788 ldrb r2, [r3]

│ ╎│ 0x0000178c ldr r3, [var_10h] ; str.

│ ╎│ ; 0x10 ; entry.preinit0

│ ╎│ 0x00001790 add r3, r3, 1

│ ╎│ 0x00001794 ldrb r3, [r3]

│ ╎│ 0x00001798 eor r3, r2, r3

│ ╎│ 0x0000179c and r2, r3, 0xff

│ ╎│ 0x000017a0 mvn r3, 0xf

│ ╎│ 0x000017a4 ldr r1, [var_14h] ; 0x14 ; entry.preinit0

│ ╎│ 0x000017a8 sub r0, fp, 0xc

│ ╎│ 0x000017ac add r1, r0, r1

│ ╎│ 0x000017b0 add r3, r1, r3

│ ╎│ 0x000017b4 strb r2, [r3]

│ ╎│ 0x000017b8 ldr r3, [var_10h] ; str.

│ ╎│ ; 0x10 ; entry.preinit0

│ ╎│ 0x000017bc add r3, r3, 2 ; "ELF\x01\x01\x01" ; aav.0x00000001

│ ╎│ 0x000017c0 str r3, [var_10h] ; str.

│ ╎│ ; 0x10

│ ╎│ 0x000017c4 ldr r3, [var_14h] ; 0x14 ; entry.preinit0

│ ╎│ 0x000017c8 add r3, r3, 1

│ ╎│ 0x000017cc str r3, [var_14h] ; 0x14

│ ╎│ ; CODE XREF from fcn.00001760 (0x1780)

│ ╎╰─> 0x000017d0 ldr r3, [var_14h] ; 0x14 ; entry.preinit0

│ ╎ 0x000017d4 cmp r3, 4 ; aav.0x00000004 ; aav.0x00000001 ; aav.0x00000001

│ ╰──< 0x000017d8 ble 0x1784 ; likely

│ 0x000017dc ldrb r4, [fp, -0x1c] ; "4"

│ 0x000017e0 bl fcn.000016f0

│ 0x000017e4 mov r3, r0

│ 0x000017e8 cmp r4, r3

│ ╭─< 0x000017ec bne 0x1854 ; likely

│ │ 0x000017f0 ldrb r4, [fp, -0x1b]

│ │ 0x000017f4 bl fcn.0000170c

│ │ 0x000017f8 mov r3, r0

│ │ 0x000017fc cmp r4, r3

│ ╭──< 0x00001800 bne 0x1854 ; likely

│ ││ 0x00001804 ldrb r4, [fp, -0x1a]

│ ││ 0x00001808 bl fcn.000016f0

│ ││ 0x0000180c mov r3, r0

│ ││ 0x00001810 cmp r4, r3

│ ╭───< 0x00001814 bne 0x1854 ; likely

│ │││ 0x00001818 ldrb r4, [fp, -0x19]

│ │││ 0x0000181c bl fcn.00001728

│ │││ 0x00001820 mov r3, r0

│ │││ 0x00001824 cmp r4, r3

│ ╭────< 0x00001828 bne 0x1854 ; likely

│ ││││ 0x0000182c ldrb r4, [fp, -0x18]

│ ││││ 0x00001830 bl fcn.00001744

│ ││││ 0x00001834 mov r3, r0

│ ││││ 0x00001838 cmp r4, r3

│ ╭─────< 0x0000183c bne 0x1854 ; likely

│ │││││ 0x00001840 ldr r3, [0x0000186c] ; [0x186c:4]=0x270 section..hash ; section..hash

│ │││││ 0x00001844 add r3, pc, r3 ; 0x1abc ; "Product activation passed. Congratulations!"

│ │││││ 0x00001848 mov r0, r3 ; 0x1abc ; "Product activation passed. Congratulations!" ;

│ │││││ 0x0000184c bl sym.imp.puts ; int puts(const char *s)

│ │││││ ; int puts("Product activation passed. Congratulations!")

│ ╭──────< 0x00001850 b 0x1864

│ ││││││ ; CODE XREFS from fcn.00001760 (0x17ec, 0x1800, 0x1814, 0x1828, 0x183c)

│ │╰╰╰╰╰─> 0x00001854 ldr r3, aav.0x00000288 ; [0x1870:4]=0x288 aav.0x00000288

│ │ 0x00001858 add r3, pc, r3 ; 0x1ae8 ; "Incorrect serial." ;

│ │ 0x0000185c mov r0, r3 ; 0x1ae8 ; "Incorrect serial." ;

│ │ 0x00001860 bl sym.imp.puts ; int puts(const char *s)

│ │ ; int puts("Incorrect serial.")

│ │ ; CODE XREF from fcn.00001760 (0x1850)

│ ╰──────> 0x00001864 sub sp, fp, 8

╰ 0x00001868 pop {r4, fp, pc} ; entry.preinit0 ; entry.preinit0 ;

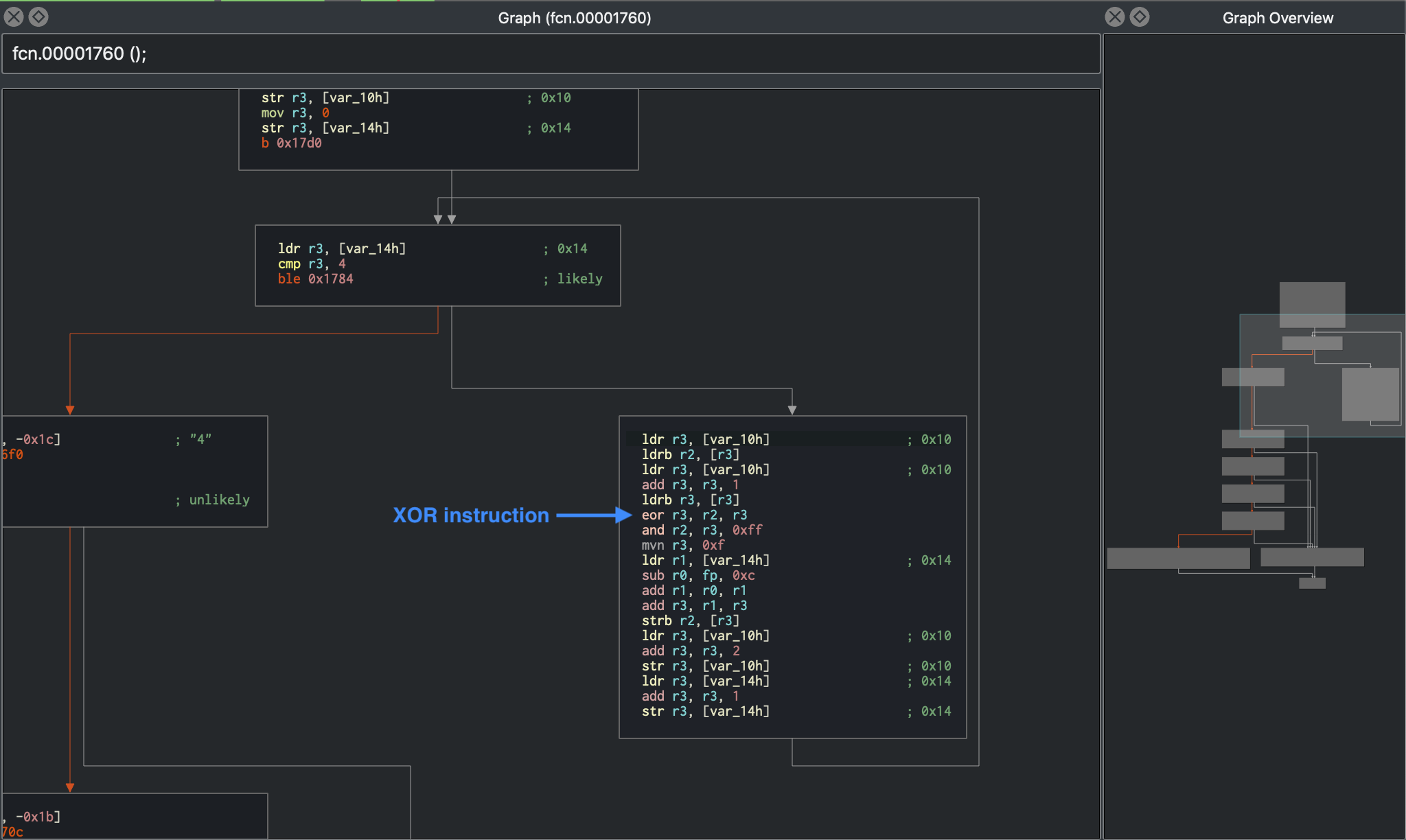

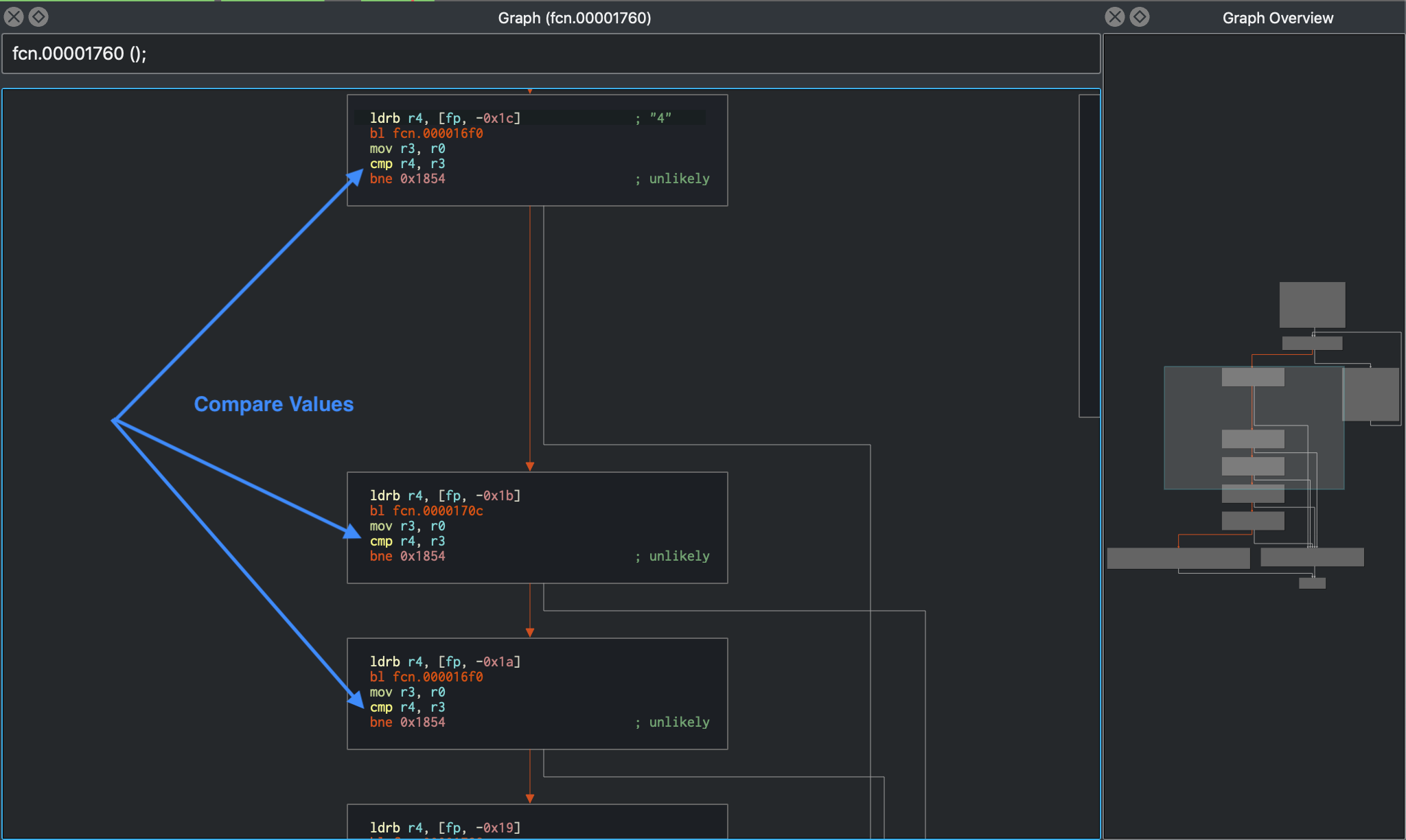

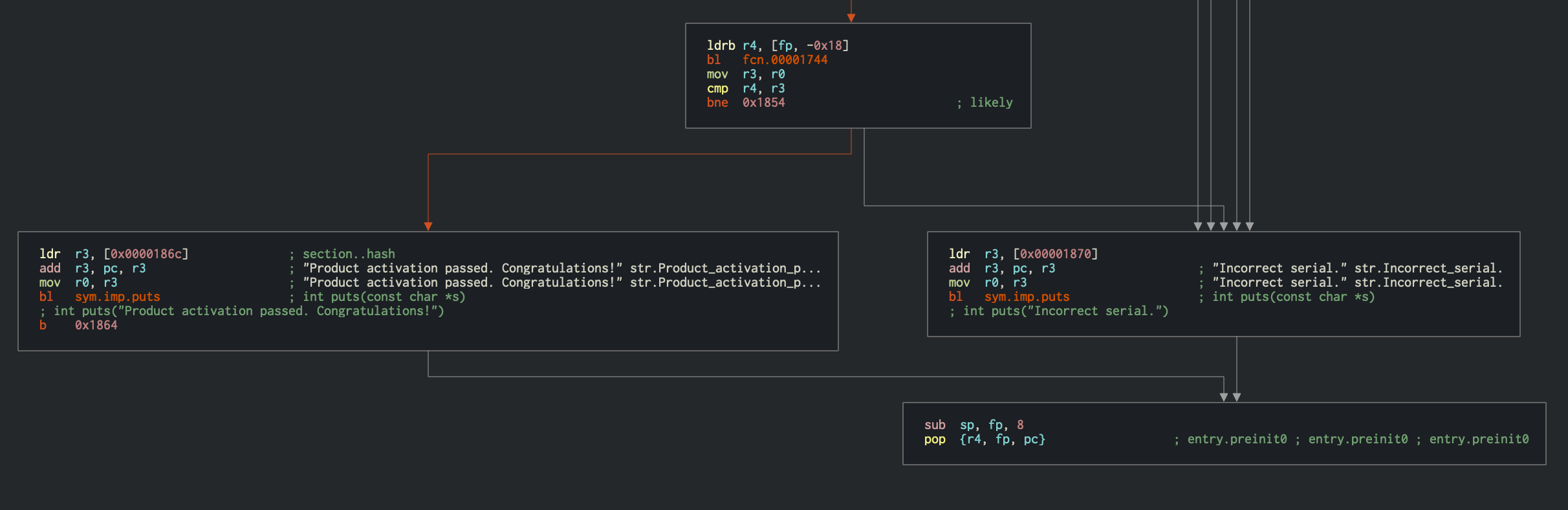

Discussing all the instructions in the function is beyond the scope of this chapter. Instead we will discuss only the important points needed for the analysis. In the validation function, there is a loop present at 0x00001784 which performs an XOR operation at offset 0x00001798. The loop is more clearly visible in the graph view below.

XOR is a very commonly used technique to encrypt information where obfuscation is the goal rather than security. XOR should not be used for any serious encryption, as it can be cracked using frequency analysis. Therefore, the mere presence of XOR encryption in such a validation logic always requires special attention and analysis.

Moving forward, at offset 0x000017dc, the XOR decoded value obtained from above is being compared against the return value from a sub-function call at 0x000017e8.

Clearly, this function is not complex and can be analyzed manually, but it still remains a cumbersome task. Especially while working on a big code base, time can be a major constraint, and it is desirable to automate such analysis. Dynamic symbolic execution is helpful in exactly those situations. In the above crackme, the symbolic execution engine can determine the constraints on each byte of the input string by mapping a path between the first instruction of the license check (at 0x00001760) and the code that prints the "Product activation passed" message (at 0x00001840).

The constraints obtained from the above steps are passed to a solver engine, which finds an input that satisfies them - a valid license key.

You need to perform several steps to initialize Angr's symbolic execution engine:

-

Load the binary into a

Project, which is the starting point for any kind of analysis in Angr. -

Pass the address from which the analysis should start. In this case, we will initialize the state with the first instruction of the serial validation function. This makes the problem significantly easier to solve because you avoid symbolically executing the Base32 implementation.

-

Pass the address of the code block that the analysis should reach. In this case, that's the offset

0x00001840, where the code responsible for printing the "Product activation passed" message is located. -

Also, specify the addresses that the analysis should not reach. In this case, the code block that prints the "Incorrect serial" message at

0x00001854is not interesting.

Note

The Angr loader will load the PIE executable with a base address of 0x400000, which needs to be added to the offsets from iaito before passing it to Angr.

The final solution script is presented below:

import angr # Version: 9.2.2

import base64

load_options = {}

b = angr.Project("./validate", load_options = load_options)

# The key validation function starts at 0x401760, so that's where we create the initial state.

# This speeds things up a lot because we're bypassing the Base32-encoder.

options = {

angr.options.SYMBOL_FILL_UNCONSTRAINED_MEMORY,

angr.options.ZERO_FILL_UNCONSTRAINED_REGISTERS,

}

state = b.factory.blank_state(addr=0x401760, add_options=options)

simgr = b.factory.simulation_manager(state)

simgr.explore(find=0x401840, avoid=0x401854)

# 0x401840 = Product activation passed

# 0x401854 = Incorrect serial

found = simgr.found[0]

# Get the solution string from *(R11 - 0x20).

addr = found.memory.load(found.regs.r11 - 0x20, 1, endness="Iend_LE")

concrete_addr = found.solver.eval(addr)

solution = found.solver.eval(found.memory.load(concrete_addr,10), cast_to=bytes)

print(base64.b32encode(solution))

The symbolic execution engine constructs a binary tree of the operations for the program input given and generates a mathematical equation for each possible path that might be taken (see Symbolic Execution). Internally, Angr explores all the paths between the two points specified by us, and passes the corresponding mathematical equations to the solver to return meaningful, concrete results. We can access these solutions via simulation_manager.found list, which contains all the possible paths explored by Angr that satisfy our specified search criteria.

Take a closer look at the latter part of the script where the final solution string is being retrieved. The address of the string is obtained from address r11 - 0x20. This may appear magical at first, but a careful analysis of the function at 0x00001760 holds the clue, as it determines if the given input string is a valid license key or not. In the disassembly above, you can see how the input string to the function (in register R0) is stored into a local stack variable 0x0000176c str r0, [var_20h]. Hence, we decided to use this value to retrieve the final solution in the script. Using found.solver.eval, you can ask the solver questions like "given the output of this sequence of operations (the current state in found), what must the input (at addr) have been?".

In ARMv7, R11 is called fp (function pointer), therefore

R11 - 0x20is equivalent tofp-0x20:var int32_t var_20h @ fp-0x20

Next, the endness parameter in the script specifies that the data is stored in "little-endian" fashion, which is the case for almost all of the Android devices.

Also, it may appear as if the script is simply reading the solution string from the memory of the script. However, it's reading it from the symbolic memory. Neither the string nor the pointer to the string actually exists. The solver ensures that the solution it provides is the same as if the program were executed to that point.

Running this script should return the following output:

$ python3 solve.py

WARNING | ... | cle.loader | The main binary is a position-independent executable. It is being loaded with a base address of 0x400000.

b'JACE6ACIARNAAIIA'

Now you can run the validate binary on your Android device to verify the solution (see Android License Validator).

You may obtain different solutions using the script, as there are multiple valid license keys possible.

To conclude, learning symbolic execution might look a bit intimidating at first, as it requires deep understanding and extensive practice. However, the effort is justified considering the valuable time it can save in contrast to analyzing complex disassembled instructions manually. Typically, you'd use hybrid techniques, as in the above example, where we performed manual analysis of the disassembled code to provide the correct criteria to the symbolic execution engine. Please refer to the iOS chapter for more examples on Angr usage.