MASTG-TECH-0018: Disassembling Native Code

Dalvik and ART both support the Java Native Interface (JNI), which defines a way for Java code to interact with native code written in C/C++. As on other Linux-based operating systems, native code is packaged (compiled) into ELF dynamic libraries (*.so), which the Android app loads at runtime via the System.load method. However, instead of relying on widely used C libraries (such as glibc), Android binaries are built against a custom libc named Bionic. Bionic adds support for important Android-specific services such as system properties and logging, and it is not fully POSIX-compatible.

When reversing an Android application containing native code, we need to understand a couple of data structures related to the JNI bridge between Java and native code. From the reverse perspective, we need to be aware of two key data structures: JavaVM and JNIEnv. Both of them are pointers to pointers to function tables:

JavaVMprovides an interface to invoke functions for creating and destroying a JavaVM. Android allows only oneJavaVMper process and is not really relevant for our reversing purposes.JNIEnvprovides access to most of the JNI functions, which are accessible at a fixed offset through theJNIEnvpointer. ThisJNIEnvpointer is the first parameter passed to every JNI function. We will discuss this concept again with the help of an example later in this chapter.

It is worth highlighting that analyzing disassembled native code is much more challenging than analyzing disassembled Java code. When reversing the native code in an Android application, we will need a disassembler.

In the next example, we'll reverse the HelloWorld-JNI.apk from the OWASP MASTG repository. Installing and running it in an emulator or Android device is optional.

wget https://github.com/OWASP/mastg/raw/master/Samples/Android/01_HelloWorld-JNI/HelloWord-JNI.apk

This app is not exactly spectacular. All it does is show a label with the text "Hello from C++". This is the app Android generates by default when you create a new project with C/C++ support, which is just enough to show the basic principles of JNI calls.

Decompile the APK with apkx.

$ apkx HelloWord-JNI.apk

Extracting HelloWord-JNI.apk to HelloWord-JNI

Converting: classes.dex -> classes.jar (dex2jar)

dex2jar HelloWord-JNI/classes.dex -> HelloWord-JNI/classes.jar

Decompiling to HelloWord-JNI/src (cfr)

This extracts the source code into the HelloWord-JNI/src directory. The main activity is found in the file HelloWord-JNI/src/sg/vantagepoint/helloworldjni/MainActivity.java. The "Hello World" text view is populated in the onCreate method:

public class MainActivity

extends AppCompatActivity {

static {

System.loadLibrary("native-lib");

}

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle bundle) {

super.onCreate(bundle);

this.setContentView(2130968603);

((TextView)this.findViewById(2131427422)).setText((CharSequence)this. \

stringFromJNI());

}

public native String stringFromJNI();

}

Note the declaration of public native String stringFromJNI at the bottom. The keyword "native" tells the Java compiler that this method is implemented in a native language. The corresponding function is resolved during runtime, but only if a native library that exports a global symbol with the expected signature is loaded (signatures comprise a package name, class name, and method name). In this example, this requirement is satisfied by the following C or C++ function:

JNIEXPORT jstring JNICALL Java_sg_vantagepoint_helloworld_MainActivity_stringFromJNI(JNIEnv *env, jobject)

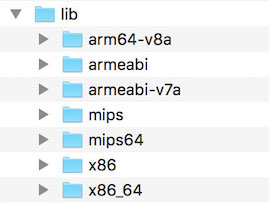

So, where is the native implementation of this function? If you look into the "lib" directory of the unzipped APK archive, you'll see several subdirectories (one per supported processor architecture), each of them containing a version of the native library, in this case libnative-lib.so. When System.loadLibrary is called, the loader selects the correct version based on the device that the app is running on. Before moving ahead, pay attention to the first parameter passed to the current JNI function. It is the same JNIEnv data structure that was discussed earlier in this section.

Following the naming convention mentioned above, you can expect the library to export a symbol called Java_sg_vantagepoint_helloworld_MainActivity_stringFromJNI. On Linux systems, you can retrieve the list of symbols with readelf (included in GNU binutils) or nm. Do this on macOS with the greadelf tool, which you can install via Macports or Homebrew. The following example uses greadelf:

$ greadelf -W -s libnative-lib.so | grep Java

3: 00004e49 112 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 11 Java_sg_vantagepoint_helloworld_MainActivity_stringFromJNI

You can also see this using radare2's rabin2:

$ rabin2 -s HelloWord-JNI/lib/armeabi-v7a/libnative-lib.so | grep -i Java

003 0x00000e78 0x00000e78 GLOBAL FUNC 16 Java_sg_vantagepoint_helloworldjni_MainActivity_stringFromJNI

This is the native function that eventually gets executed when the stringFromJNI native method is called.

To disassemble the code, you can load libnative-lib.so into any disassembler that understands ELF binaries (i.e., any disassembler). If the app ships with binaries for different architectures, you can theoretically pick the architecture you're most familiar with, as long as it is compatible with the disassembler. Each version is compiled from the same source and implements the same functionality. However, if you're planning to debug the library on a live device later, it's usually wise to pick an ARM build.

To support both older and newer ARM processors, Android apps ship with multiple ARM builds compiled for different Application Binary Interface (ABI) versions. The ABI defines how the application's machine code is supposed to interact with the system at runtime. The following ABIs are supported:

- armeabi: ABI is for ARM-based CPUs that support at least the ARMv5TE instruction set.

- armeabi-v7a: This ABI extends armeabi to include several CPU instruction set extensions.

- arm64-v8a: ABI for ARMv8-based CPUs that support AArch64, the new 64-bit ARM architecture.

Most disassemblers can handle any of those architectures. Below, we'll be viewing the armeabi-v7a version (located in HelloWord-JNI/lib/armeabi-v7a/libnative-lib.so) in radare2 and in IDA Pro. See Reviewing Disassembled Native Code to learn how to proceed when inspecting the disassembled native code.

radare2¶

To open the file in radare2 for Android, you only have to run r2 -A HelloWord-JNI/lib/armeabi-v7a/libnative-lib.so. The chapter "Android Basic Security Testing" already introduced radare2. Remember that you can use the flag -A to run the aaa command right after loading the binary in order to analyze all referenced code.

$ r2 -A HelloWord-JNI/lib/armeabi-v7a/libnative-lib.so

[x] Analyze all flags starting with sym. and entry0 (aa)

[x] Analyze function calls (aac)

[x] Analyze len bytes of instructions for references (aar)

[x] Check for objc references

[x] Check for vtables

[x] Finding xrefs in noncode section with anal.in=io.maps

[x] Analyze value pointers (aav)

[x] Value from 0x00000000 to 0x00001dcf (aav)

[x] 0x00000000-0x00001dcf in 0x0-0x1dcf (aav)

[x] Emulate code to find computed references (aae)

[x] Type matching analysis for all functions (aaft)

[x] Use -AA or aaaa to perform additional experimental analysis.

-- Print the contents of the current block with the 'p' command

[0x00000e3c]>

Note that for bigger binaries, starting directly with the flag -A might be very time-consuming as well as unnecessary. Depending on your purpose, you may open the binary without this option and then apply a less complex analysis like aa or a more concrete type of analysis, such as the ones offered in aa (basic analysis of all functions) or aac (analyze function calls). Remember to always type ? to get help or attach it to commands to see even more commands or options. For example, if you enter aa?, you'll get the full list of analysis commands.

[0x00001760]> aa?

Usage: aa[0*?] # see also 'af' and 'afna'

| aa alias for 'af@@ sym.*;af@entry0;afva'

| aaa[?] autoname functions after aa (see afna)

| aab abb across bin.sections.rx

| aac [len] analyze function calls (af @@ `pi len~call[1]`)

| aac* [len] flag function calls without performing a complete analysis

| aad [len] analyze data references to code

| aae [len] ([addr]) analyze references with ESIL (optionally to address)

| aaf[e|t] analyze all functions (e anal.hasnext=1;afr @@c:isq) (aafe=aef@@f)

| aaF [sym*] set anal.in=block for all the spaces between flags matching glob

| aaFa [sym*] same as aaF but uses af/a2f instead of af+/afb+ (slower but more accurate)

| aai[j] show info of all analysis parameters

| aan autoname functions that either start with fcn.* or sym.func.*

| aang find function and symbol names from golang binaries

| aao analyze all objc references

| aap find and analyze function preludes

| aar[?] [len] analyze len bytes of instructions for references

| aas [len] analyze symbols (af @@= `isq~[0]`)

| aaS analyze all flags starting with sym. (af @@ sym.*)

| aat [len] analyze all consecutive functions in section

| aaT [len] analyze code after trap-sleds

| aau [len] list mem areas (larger than len bytes) not covered by functions

| aav [sat] find values referencing a specific section or map

There is a thing that is worth noticing about radare2 vs other disassemblers, like IDA Pro, for example. The following quote from this article of radare2's blog (https://radareorg.github.io/blog/) offers a good summary.

Code analysis is not a quick operation, and it is not even predictable or take linear time to be processed. This makes starting times pretty heavy, compared to just loading the headers and strings information, like it's done by default.

People who are used to IDA Pro or Hopper just load the binary, go out to make a coffee, and then, when the analysis is done, they start doing the manual analysis to understand what the program is doing. It's true that those tools perform the analysis in the background, and the GUI is not blocked. But this takes a lot of CPU time, and r2 aims to run on many more platforms than just high-end desktop computers.

This said, please see Reviewing Disassembled Native Code to learn more bout how radare2 can help us perform our reversing tasks much faster. For example, getting the disassembly of a specific function is a trivial task that can be performed in one command.

IDA Pro¶

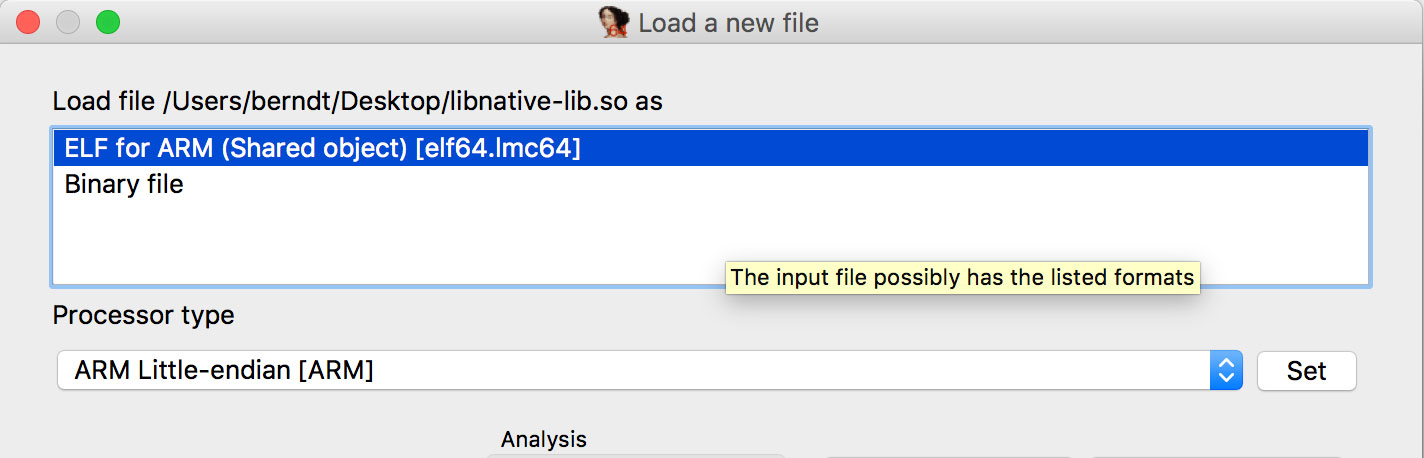

If you own an IDA Pro license, open the file and once in the "Load new file" dialog, choose "ELF for ARM (Shared Object)" as the file type (IDA should detect this automatically), and "ARM Little-Endian" as the processor type.

The freeware version of IDA Pro unfortunately does not support the ARM processor type.