Mobile App Cryptography¶

Cryptography plays an especially important role in securing the user's data - even more so in a mobile environment, where attackers having physical access to the user's device is a likely scenario. This chapter provides an outline of cryptographic concepts and best practices relevant to mobile apps. These best practices are valid independent of the mobile operating system.

Key Concepts¶

The goal of cryptography is to provide constant confidentiality, data integrity, and authenticity, even in the face of an attack. Confidentiality involves ensuring data privacy through the use of encryption. Data integrity deals with data consistency and detection of tampering and modification of data through the use of hashing. Authenticity ensures that the data comes from a trusted source.

An encryption algorithm converts plaintext data into ciphertext, which conceals the original content. The plaintext data can be restored from the ciphertext through decryption. There are two types of encryption: symmetric (encryption and decryption use the same secret key) and asymmetric (encryption and decryption use a public and private key pair). Symmetric encryption operations do not protect data integrity unless they are used with an approved cipher mode that supports authenticated encryption with a random initialization vector (IV) that fulfills the "uniqueness" requirement NIST SP 800-38D - "Recommendation for Block Cipher Modes of Operation: Galois/Counter Mode (GCM) and GMAC", 2007.

Symmetric-key encryption algorithms use the same key for both encryption and decryption. This type of encryption is fast and suitable for bulk data processing. Since everybody who has access to the key is able to decrypt the encrypted content, this method requires careful key management and centralized control over key distribution.

Public-key encryption algorithms operate with two separate keys: the public key and the private key. The public key can be distributed freely while the private key shouldn't be shared with anyone. A message encrypted with the public key can only be decrypted with the private key and vice-versa. Since asymmetric encryption is several times slower than symmetric operations, it's typically only used to encrypt small amounts of data, such as symmetric keys for bulk encryption.

Hashing isn't a form of encryption, but it does use cryptography. Hash functions map arbitrary pieces of data into fixed-length values in a deterministic way. While it's easy to compute the hash from the input, it's very difficult (i.e., infeasible) to determine the original input from the hash. Additionally, the hash changes completely when even a single bit of the input changes. Hash functions are used for storing passwords, verifying integrity (e.g., digital signatures or document management), and managing files. Although hash functions don't provide an authenticity guarantee, they can be combined as cryptographic primitives to do so.

Message Authentication Codes (MACs) combine other cryptographic mechanisms (such as symmetric encryption or hashes) with secret keys to provide both integrity and authenticity protection. However, in order to verify a MAC, multiple entities have to share the same secret key and any of those entities can generate a valid MAC. HMACs, the most commonly used type of MAC, rely on hashing as the underlying cryptographic primitive. The full name of an HMAC algorithm usually includes the underlying hash function's type (for example, HMAC-SHA256 uses the SHA-256 hash function).

Signatures combine asymmetric cryptography (that is, using a public/private key pair) with hashing to provide integrity and authenticity by encrypting the hash of the message with the private key. However, unlike MACs, signatures also provide non-repudiation property as the private key should remain unique to the data signer.

Key Derivation Functions (KDFs) derive secret keys from a secret value (such as a password) and are used to turn keys into other formats or to increase their length. KDFs are similar to hashing functions but have other uses as well (for example, they are used as components of multi-party key-agreement protocols). While both hashing functions and KDFs must be difficult to reverse, KDFs have the added requirement that the keys they produce must have a level of randomness.

Identifying Insecure and/or Deprecated Cryptographic Algorithms¶

When assessing a mobile app, you should make sure that it does not use cryptographic algorithms and protocols that have significant known weaknesses or are otherwise insufficient for modern security requirements. Algorithms that were considered secure in the past may become insecure over time; therefore, it's important to periodically check current best practices and adjust configurations accordingly.

Verify that cryptographic algorithms are up to date and in-line with industry standards. Vulnerable algorithms include outdated block ciphers (such as DES and 3DES), stream ciphers (such as RC4), hash functions (such as MD5 and SHA1), and broken random number generators (such as Dual_EC_DRBG and SHA1PRNG). Note that even algorithms that are certified (for example, by NIST) can become insecure over time. A certification does not replace periodic verification of an algorithm's soundness. Algorithms with known weaknesses should be replaced with more secure alternatives. Additionally, algorithms used for encryption must be standardized and open to verification. Encrypting data using any unknown, or proprietary algorithms may expose the application to different cryptographic attacks which may result in recovery of the plaintext.

Inspect the app's source code to identify instances of cryptographic algorithms that are known to be weak, such as:

The names of cryptographic APIs depend on the particular mobile platform.

Please make sure that:

- Cryptographic algorithms are up to date and in-line with industry standards. This includes, but is not limited to outdated block ciphers (e.g. DES), stream ciphers (e.g. RC4), as well as hash functions (e.g. MD5) and broken random number generators like Dual_EC_DRBG (even if they are NIST certified). All of these should be marked as insecure and should not be used and removed from the application and server.

- Key lengths are in line with industry standards and provide sufficient protection over a long period of time. A comparison of different key lengths and the protection they provide, taking Moore's Law into account, is available online.

- Through NIST SP 800-131A - "Transitioning the Use of Cryptographic Algorithms and Key Lengths", 2024, NIST provides recommendations and guidance on aligning with future recommendations and transitioning to stronger cryptographic keys and more robust algorithms.

- Cryptographic means are not mixed with each other: e.g. you do not sign with a public key, or try to reuse a key pair used for a signature to do encryption.

- Cryptographic parameters are well defined within reasonable range. This includes, but is not limited to: cryptographic salt, which should be at least the same length as hash function output, reasonable choice of password derivation function and iteration count (e.g. PBKDF2, scrypt or bcrypt), IVs being random and unique, fit-for-purpose block encryption modes (e.g. ECB should not be used, except specific cases), key management being done properly (e.g. 3DES should have three independent keys) and so on.

Recommended algorithms:

- Confidentiality algorithms: AES-GCM-256 or ChaCha20-Poly1305

- Integrity algorithms: SHA-256, SHA-384, SHA-512, BLAKE3, the SHA-3 family

- Digital signature algorithms: RSA (3072 bits and higher), ECDSA with NIST P-384 or EdDSA with Edwards448.

- Key establishment algorithms: RSA (3072 bits and higher), DH (3072 bits or higher), ECDH with NIST P-384

Note

The recommendations are based on the current industry perception of what is considered appropriate. They align with NIST recommendations beyond 2030, but do not necessarily account for advancements in quantum computing. For advice on post-quantum cryptography, please see the "Post-Quantum" section below.

Additionally, you should always rely on secure hardware (if available) for storing encryption keys, performing cryptographic operations, etc.

For more information on algorithm choice and best practices, see the following resources:

- "Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite and Quantum Computing FAQ"

- NIST recommendations (2019)

- BSI recommendations (2019)

- NIST SP 800-56B Revision 2 - "Recommendation for Pair-Wise Key-Establishment Using Integer Factorization Cryptography", 2019: NIST advises using RSA-based key-transport schemes with a minimum modulus length of at least 2048 bits.

- NIST SP 800-56A Revision 3 - "Recommendation for Pair-Wise Key-Establishment Schemes Using Discrete Logarithm Cryptography", 2018: NIST advises using ECC-based key-agreement schemes, such as Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH), utilizing curves from P-224 to P-521.

- FIPS 186-5 - "Digital Signature Standard (DSS)", 2023: NIST approves RSA, ECDSA, and EdDSA for digital signature generation. DSA should only be used to verify previously generated signatures.

- NIST SP 800-186 - "Recommendations for Discrete Logarithm-Based Cryptography: Elliptic Curve Domain Parameters", 2023: Provides recommendations for elliptic curve domain parameters used in discrete logarithm-based cryptography.

Post-Quantum¶

Public-Key Encryption Algorithms¶

In 2024, NIST approved CRYSTALS-Kyber as a post-quantum key encapsulation mechanism (KEM) for establishing a shared secret over a public channel. This shared secret can then be used with symmetric-key algorithms for encryption and decryption.

- FIPS 203 - "Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism Standard", 2024: Specifies CRYSTALS-Kyber as the standard for post-quantum key encapsulation.

Signatures¶

In 2024, NIST approved SLH-DSA and ML-DSA as recommended digital signature algorithms for post-quantum signature generation and verification.

- FIPS 205 - "Stateless Hash-Based Digital Signature Standard", 2024: Specifies SLH-DSA for post-quantum digital signatures.

- FIPS 204 - "Module-Lattice-Based Digital Signature Standard", 2024: Specifies ML-DSA for post-quantum digital signatures.

Common Configuration Issues¶

Insufficient Key Length¶

Even the most secure encryption algorithm becomes vulnerable to brute-force attacks when that algorithm uses an insufficient key size.

Ensure that the key length fulfills accepted industry standards.

Symmetric Encryption with Hard-Coded Cryptographic Keys¶

The security of symmetric encryption and keyed hashes (MACs) depends on the secrecy of the key. If the key is disclosed, the security gained by encryption is lost. To prevent this, never store secret keys in the same place as the encrypted data they helped create. A common mistake is encrypting locally stored data with a static, hardcoded encryption key and compiling that key into the app. This makes the key accessible to anyone who can use a disassembler.

Hardcoded encryption key means that a key is:

- part of application resources

- value which can be derived from known values

- hardcoded in code

First, ensure that no keys or passwords are stored within the source code. This means you should check native code, JavaScript/Dart code, Java/Kotlin code on Android and Objective-C/Swift in iOS. Note that hard-coded keys are problematic even if the source code is obfuscated since obfuscation is easily bypassed by dynamic instrumentation.

If the app is using two-way TLS (both server and client certificates are validated), make sure that:

- The password to the client certificate isn't stored locally or is locked in the device Keychain.

- The client certificate isn't shared among all installations.

If the app relies on an additional encrypted container stored in app data, check how the encryption key is used. If a key-wrapping scheme is used, ensure that the master secret is initialized for each user or the container is re-encrypted with new key. If you can use the master secret or previous password to decrypt the container, check how password changes are handled.

Secret keys must be stored in secure device storage whenever symmetric cryptography is used in mobile apps. For more information on the platform-specific APIs, see the "Data Storage on Android" and "Data Storage on iOS" chapters.

Improper Key Derivation Functions¶

Cryptographic algorithms (such as symmetric encryption or some MACs) expect a secret input of a given size. For example, AES uses a key of exactly 16 bytes. A native implementation might use the user-supplied password directly as an input key. Using a user-supplied password as an input key has the following problems:

- If the password is smaller than the key, the full key space isn't used. The remaining space is padded (spaces are sometimes used for padding).

- A user-supplied password will realistically consist mostly of displayable and pronounceable characters. Therefore, only some of the possible 256 ASCII characters are used and entropy is decreased by approximately a factor of four.

Ensure that passwords aren't directly passed into an encryption function. Instead, the user-supplied password should be passed into a KDF to create a cryptographic key. Choose an appropriate iteration count when using password derivation functions. For example, NIST recommends an iteration count of at least 10,000 for PBKDF2 and for critical keys where user-perceived performance is not critical at least 10,000,000. For critical keys, it is recommended to consider implementation of algorithms recognized by Password Hashing Competition (PHC) like Argon2.

Improper Random Number Generation¶

A common weakness in mobile apps is the improper use of random number generators. Regular Pseudo-Random Number Generators (PRNGs), while sufficient for general use, are not designed for cryptographic purposes. When used to generate keys, tokens, or other security-critical values, they can make systems vulnerable to prediction and attack.

The root issue is that deterministic devices cannot produce true randomness. PRNGs simulate randomness using algorithms, but without sufficient entropy and algorithmic strength, the output can be predictable. For example, UUIDs may appear random but do not provide enough entropy for secure use.

The correct approach is to use a Cryptographically Secure Pseudo-Random Number Generator (CSPRNG). CSPRNGs are designed to resist statistical analysis and prediction, making them suitable for generating non-guessable values. All security-sensitive values must be generated using a CSPRNG with at least 128 bits of entropy.

Improper Hashing¶

Using the wrong hash function for a given purpose can compromise both security and data integrity. Each hash function is designed with specific use cases in mind, and applying it incorrectly introduces risk.

For integrity checks, choose a hash function that offers strong collision resistance. Algorithms such as SHA-256, SHA-384, SHA-512, BLAKE3, and the SHA-3 family are appropriate for verifying data integrity and authenticity. Avoid broken algorithms like MD5 or SHA-1, as they are vulnerable to collision attacks.

Do not use general-purpose hash functions like SHA-2 or SHA-3 for password hashing or key derivation, especially with predictable input.

Custom Implementations of Cryptography¶

Inventing proprietary cryptographic functions is time-consuming, difficult, and likely to fail. Instead, we can use well-known algorithms that are widely regarded as secure. Mobile operating systems offer standard cryptographic APIs that implement those algorithms.

Carefully inspect all the cryptographic methods used within the source code, especially those that are directly applied to sensitive data. All cryptographic operations should use standard cryptographic APIs for Android and iOS (we'll write about those in more detail in the platform-specific chapters). Any cryptographic operations that don't invoke standard routines from known providers should be closely inspected. Pay close attention to standard algorithms that have been modified. Remember that encoding isn't the same as encryption! Always investigate further when you find bit manipulation operators like XOR (exclusive OR).

In all implementations of cryptography, you need to ensure that the following always takes place:

- Working keys (like intermediary/derived keys in AES/DES/Rijndael) are properly removed from memory after consumption or in case of error.

- The inner state of a cipher should be removed from memory as soon as possible.

Improper Encryption¶

Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) is the widely accepted standard for symmetric encryption in mobile apps. It's an iterative block cipher that is based on a series of linked mathematical operations. AES performs a variable number of rounds on the input, each of which involve substitution and permutation of the bytes in the input block. Each round uses a 128-bit round key which is derived from the original AES key.

As of this writing, no efficient cryptanalytic attacks against AES have been discovered. However, implementation details and configurable parameters such as the block cipher mode leave some margin for error.

Broken Block Cipher Modes¶

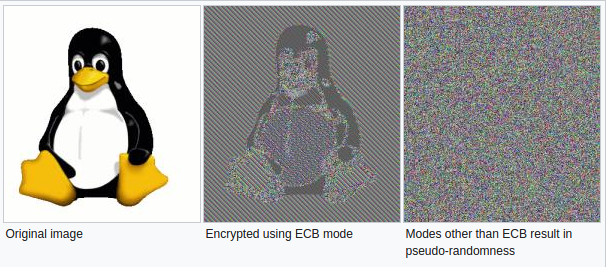

Block-based encryption is performed upon discrete input blocks (for example, AES has 128-bit blocks). If the plaintext is larger than the block size, the plaintext is internally split up into blocks of the given input size and encryption is performed on each block. A block cipher mode of operation (or block mode) determines if the result of encrypting the previous block impacts subsequent blocks.

Avoid using the ECB (Electronic Codebook) mode. ECB divides the input into fixed-size blocks that are encrypted separately using the same key. If multiple divided blocks contain the same plaintext, they will be encrypted into identical ciphertext blocks which makes patterns in data easier to identify. In some situations, an attacker might also be able to replay the encrypted data.

For new designs, prefer authenticated encryption with associated data (AEAD) modes such as Galois/Counter Mode (GCM) or Counter with CBC-MAC (CCM), as these provide both confidentiality and integrity. If GCM or CCM are not available, Cipher Block Chaining (CBC) mode is better than ECB, but should be combined with an HMAC and/or ensure that no errors are given such as "Padding error", "MAC error", or "decryption failed" to be more resistant to padding oracle attacks. In CBC mode, plaintext blocks are XORed with the previous ciphertext block, ensuring that each encrypted block is unique and randomized even if blocks contain the same information.

When storing encrypted data, we recommend using a block mode that also protects the integrity of the stored data, such as Galois/Counter Mode (GCM). The latter has the additional benefit that the algorithm is mandatory for each TLSv1.2 implementation, and thus is available on all modern platforms. To protect the integrity and authenticity of the data using CBC mode, it is recommended to combine the techniques of the Counter (CTR) mode and the Cipher Block Chaining-Message Authentication Code (CBC-MAC) into what is called CCM Mode (NIST, 2004).

For more information on effective block modes, see the NIST guidelines on block mode selection.

Predictable Initialization Vector¶

CBC, OFB, CFB, PCBC, GCM mode require an initialization vector (IV) as an initial input to the cipher. The IV doesn't have to be kept secret, but it shouldn't be predictable: it should be random and unique/non-repeatable for each encrypted message. Make sure that IVs are generated using a cryptographically secure random number generator. For more information on IVs, see Crypto Fail's initialization vectors article.

Pay attention to cryptographic libraries used in the code: many open source libraries provide examples in their documentations that might follow bad practices (e.g. using a hardcoded IV). A popular mistake is copy-pasting example code without changing the IV value.

Using the Same Key for Encryption and Authentication¶

One common mistake is to reuse the same key for CBC encryption and CBC-MAC. Reuse of keys for different purposes is generally not recommended, but in the case of CBC-MAC the mistake can lead to a MitM attack ("CBC-MAC", 2024.10.11).

Initialization Vectors in Stateful Operation Modes¶

Please note that the usage of IVs is different when using CTR and GCM mode in which the initialization vector is often a counter (in CTR combined with a nonce). So here using a predictable IV with its own stateful model is exactly what is needed. In CTR you have a new nonce plus counter as an input to every new block operation. For example: for a 5120 bit long plaintext: you have 20 blocks, so you need 20 input vectors consisting of a nonce and counter. Whereas in GCM you have a single IV per cryptographic operation, which should not be repeated with the same key. See section 8 of the documentation from NIST on GCM for more details and recommendations of the IV.

Padding Oracle Attacks due to Weaker Padding or Block Operation Implementations¶

In the old days, PKCS1.5 padding (in code: PKCS1Padding) was used as a padding mechanism when doing asymmetric encryption. This mechanism is vulnerable to the padding oracle attack. Therefore, it is best to use OAEP (Optimal Asymmetric Encryption Padding) captured in PKCS#1 v2.0 (in code: OAEPPadding, OAEPwithSHA-256andMGF1Padding, OAEPwithSHA-224andMGF1Padding, OAEPwithSHA-384andMGF1Padding, OAEPwithSHA-512andMGF1Padding). Note that, even when using OAEP, you can still run into an issue known best as the Manger's attack as described in the blog at Kudelskisecurity.

Note: AES-CBC with PKCS #7 has shown to be vulnerable to padding oracle attacks as well, given that the implementation gives warnings, such as "Padding error", "MAC error", or "decryption failed". See The Padding Oracle Attack and The CBC Padding Oracle Problem for an example. Next, it is best to ensure that you add an HMAC after you encrypt the plaintext: after all a ciphertext with a failing MAC will not have to be decrypted and can be discarded.

Protecting Keys in Storage and in Memory¶

When memory dumping is part of your threat model, then keys can be accessed the moment they are actively used. Memory dumping either requires root-access (e.g. a rooted device or jailbroken device) or it requires a patched application with Frida (so you can use tools like Fridump). Therefore it is best to consider the following, if keys are still needed at the device:

- Keys in a Remote Server: you can use remote Key vaults such as Amazon KMS or Azure Key Vault. For some use cases, developing an orchestration layer between the app and the remote resource might be a suitable option. For instance, a serverless function running on a Function as a Service (FaaS) system (e.g. AWS Lambda or Google Cloud Functions) which forwards requests to retrieve an API key or secret. There are other alternatives such as Amazon Cognito, Google Identity Platform or Azure Active Directory.

- Keys inside Secure Hardware-backed Storage: make sure that all cryptographic actions and the key itself remain in the Trusted Execution Environment (e.g. use Android Keystore) or Secure Enclave (e.g. use the Keychain). Refer to the Android Data Storage and iOS Data Storage chapters for more information.

- Keys protected by Envelope Encryption: If keys are stored outside of the TEE / SE, consider using multi-layered encryption: an envelope encryption approach (see OWASP Cryptographic Storage Cheat Sheet, Google Cloud Key management guide, AWS Well-Architected Framework guide), or a HPKE approach to encrypt data encryption keys with key encryption keys.

- Keys in Memory: make sure that keys live in memory for the shortest time possible and consider zeroing out and nullifying keys after successful cryptographic operations, and in case of error. Note: In some languages and platforms (such as those with garbage collection or memory management optimizations), reliably zeroing memory may not be possible, as the runtime may move or copy memory or delay actual erasure. For general cryptocoding guidelines, refer to Clean memory of secret data.

Note: given the ease of memory dumping, never share the same key among accounts and/or devices, other than public keys used for signature verification or encryption.

Protecting Keys in Transport¶

When keys need to be transported from one device to another, or from the app to a backend, make sure that proper key protection is in place, by means of a transport keypair or another mechanism. Often, keys are shared with obfuscation methods which can be easily reversed. Instead, make sure asymmetric cryptography or wrapping keys are used. For example, a symmetric key can be encrypted with the public key from an asymmetric key pair.

Cryptographic APIs on Android and iOS¶

While same basic cryptographic principles apply independent of the particular OS, each operating system offers its own implementation and APIs. Platform-specific cryptographic APIs for data storage are covered in greater detail in the "Data Storage on Android" and "Testing Data Storage on iOS" chapters. Encryption of network traffic, especially Transport Layer Security (TLS), is covered in the "Android Network APIs" chapter.

Cryptographic Policy¶

In larger organizations, or when high-risk applications are created, it can often be a good practice to have a cryptographic policy, based on frameworks such as NIST Recommendation for Key Management. When basic errors are found in the application of cryptography, it can be a good starting point of setting up a lessons learned / cryptographic key management policy.

Cryptography Regulations¶

When you upload the app to the App Store or Google Play, your application is typically stored on a US server. If your app contains cryptography and is distributed to any other country, it is considered a cryptography export. It means that you need to follow US export regulations for cryptography. Also, some countries have import regulations for cryptography.

Learn more: